Gender, race, class and art history occupy most part of the

course of mankind. And artists of different background have demonstrated a

greater commitment to this course by projecting the unearned privileges that

seem to sustain inequality among people and societies. So art spans the entire history of humankind,

from prehistoric times to the twenty-first century. Nevertheless, Chadwick

notes that “any study of women artists must examine how art history is written”

and it is with strong passion for arts that most of the artists, notably Alice

Barbara Stephens, Mary Ellen Mark, Sofoniba Anguissola, Gertrude Käsebier and

Marina Abramović have embarked on separate artistic agenda to bring to bear

various issues of concern and also to project the role of arts in society

(17). They have for years been

influential in 19th century American Arts- Angels and Tomboys, Woman Behind and

in front of the camera, Renaissance, feminism and performance arts respectively.

Angels & Tomboys: Girlhood in 19th-Century American Art

is a major traveling loan exhibition, which is the first to examine

nineteenth-century depictions of girls in paintings, sculpture, prints and

photographs. The exhibition analyzes the

myriad ways that artists vigorously participated in the artistic and social

construction of girlhood while also revealing the hopes and fears that adults

had for their children. While the sentimental portrayal of girls as angelic,

passive and domestic was the pervasive characterization, this project also identifies

and analyses compelling and transgressive female images including tomboys,

working children and adolescents. In the aftermath of the Civil War, the

American girl seemed transformed—at once more introspective and adventurous

than her counterpart of the previous generation. She took center stage in the

stories of Louisa May Alcott and Henry James at the same moment that

contemporary painters, illustrators, photographers, and sculptors asked her to

pose. For the first time, girls claimed the attention of genre artists, and

girlhood itself seized the imagination of the nation. Although the culture

still prized the demure female child of the past, many saw a bolder type as the

new, alternate ideal. Girlhood was no longer simple, and the complementary images

of angel and tomboy emerged as competing visions of this new generation.

Alice Barber Stephens, 1858 – 1932

Alice Barber was born on a farm near Salem, NJ, where she

attended local schools. The family moved to Philadelphia, and by 1873 she was a

full time student at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now Moore

College of Art). There she became proficient at engraving, an important skill

in the days before photo-mechanical reproduction. In 1876 she enrolled at the

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where she studied under Thomas Eakins.

Among her classmates was Emily Sartain. Financial considerations finally forced

her to turn to full-time engraving, but by 1885, the long hours and close work

affected her health. She turned to pen and ink drawing and was soon supporting

herself by illustration in that medium. During a trip to Europe she took up

painting in oils. When she returned, she supported herself with pen and ink

illustration and painted for relaxation.

In 1890 she married another fellow Academy student, Charles

Hallowell Stephens, by this time a teacher at the Academy. She continued to

work as an illustrator, now in color and with a softer effect produced by paint

instead of pen and ink. Her talents were equally effective in the domestic

genre stories then popular in magazines, and with more dramatic illustrations

for works by Conan Doyle. With Emily Sartain, Alice Barber Stephens was one of

the founders of The Plastic club in 1897. She served as vice president every

year from 1897 through 1912. Stephens was also active in the establishment of

the Fellowship of the Academy of fine Arts, and served on the Board for several

years. Her career spanned fifty years, during which time she earned the respect

of her fellow artists, male and female. She was active in lecturing and

teaching, and in demand as a judge of art and photography. There were numerous

exhibitions of her work during her lifetime. In 1984, more than 50 years after

her death, the Brandywine River Museum held an exhibition of her work.

“The woman in Business”, 1897

Rich consumers and the working poor are contrasted in this

powerful grisaille, a painting composed of just black, grey, brown and white.

Set in the cavernous interior of John Wanamaker’s Philadelphia department

store, this scene includes a juvenile shop assistant with a sad, serious and

retired expression in the foreground juxtaposed to a fashionably dressed

shopper reviewing merchandise behind her.

Mary Ellen Mark, Christian Bikers, Arizona, 1988

Finding inspiration in the outer fringes of society,

photographer Mary Ellen Mark is known for her highly humanistic images. Born in

1940 in Philadelphia, Mark attended the University of Pennsylvania earning a

B.F.A in art history and painting and an M.A. in photojournalism. She has won

numerous awards for her work, including the Cornell Capa Award from the

International Center of Photography in 2001. Mark has photographed a diverse

range of subjects, including homeless families, Bombay prostitutes, Seattle

runaways, drug addicts, and the sick. In

stark contrast, Mark has also photographed actors and directors, shooting

primarily on Hollywood movie sets. Many of these images, intended for

reproduction in periodicals, have earned Mark recognition in the media world in

addition to the art world. Shooting primarily in black and white, Mark provides

the viewer a chance to look at other worlds outside their own

Mary Ellen Mark

“Private School, Miami”, 1986

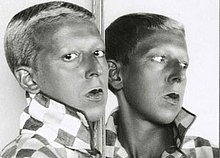

“Sisters-Christian Bikers, Arizona”, 1988

Both photographs by Mary Mark depict adolescent girls from

different parts of the United States. The subjects’ shyness is obvious.

Nonetheless, these girls do not hide their insecurities or mask their

awkwardness. Mark captures their vulnerability, noticeable especially by the

girls wearing their school uniforms; their body language, restrained similes

and stern gazes suggest certain timidity. The two sisters leaning on the

motorcycle convey a tougher appearance and confidence, particularly the girl on

the right. Her piercing eyes, hairstyle and posture grant her a tomboyish look

and she appears as though she owns the vehicle. It is evident from these images

that the photographer established a close relationship to her subjects.

Sofoniba Anguissola- Renaissance Painter

Renaissance movement that took place from roughly 1300 to

1500 also meant “rebirth,” and the term “Renaissance Man” was coined.

“Renaissance Man” is still used to today to describe a person who is creative,

artistic, musical, and worldly and can seemingly be able and willing to do it

all. Not until the sixteenth century did a few women manage to turn the new

Renaissance emphasis on virtue and gentility into positive attributes for the

women artists. Therefore, Guerilla Girls notes that if a “woman wanted to be

work as an artist, she most likely would have had to be born into a family of

nobility” (29). Many women of the Renaissance were illiterate or not well

educated. They couldn’t make their own money and seemed to survive through

marriage and raising a family.

The woman’s role in the Renaissance was to be a

child-bearer, a keeper of the home and a good wife. The family as a unit was

vital to Italian society, and the class system of these families was in full

effect. The Renaissance masters represented the woman’s role in very

interesting and strange ways within their paintings. Even though women were seen as domestic

creatures, rarely were they depicted in domestic settings. Instead, they were

shown as Biblical figures, in high society portraiture or, most interesting of

all, as nudes portrayed in a very sexual manner. These representations are

almost the exact opposite of their daily role and this could be an interesting

examination on the psychology of the Renaissance male artist. It is possible

that the representation of women were projections of what men wanted

Renaissance women to be, or an unconscious rebellion of what society was like

at that time. Whatever the reason, the depictions of women during the

Renaissance are vital to the study of women in art as they reveal the way

Renaissance life was and how women were viewed during these years.

Sofonisba Anguissola was a rare exception and was the best

known of the sisters, she was trained, with Elena, by Bernardino Campi and

Gatti. Most of Vasari's account of his visit to the Anguissola family is

devoted to Sofonisba, about whom he wrote: 'Anguissola has shown greater

application and better grace than any other woman of our age in her endeavours

at drawing; she has thus succeeded not only in drawing, colouring and painting

from nature, and copying excellently from others, but by herself has created

rare and very beautiful paintings'. Sofonisba's privileged background was

unusual among woman artists of the 16th century, most of whom, like Lavinia

Fontana, Fede Galizia and Barbara Longhi, were daughters of painters. Her

social class did not, however, enable her to transcend the constraints of her

sex. Without the possibility of studying anatomy, or drawing from life, she

could not undertake the complex multi-figure compositions required for

large-scale religious or history paintings. She turned instead to the models

accessible to her, exploring a new type of portraiture with sitters in informal

domestic settings. Aristocratic, intelligent, extraordinarily well-connected,

she amazed all her contemporaries. Her self-portraits and portraits of her

family are considered her finest works; they are somewhat stiff, but can have

great charm. Chadwick, in reference to Anguissola maintains, that “the first

woman painter to achieve fame and respect did so within a set of constraints

that removed her from competing for commissions with her male contemporaries

and that effectively placed her within in a critical category of her own” (79).

Being a female artist her achievements were even more extraordinary considering

the social attitudes of her time to the notion of a female as artist.

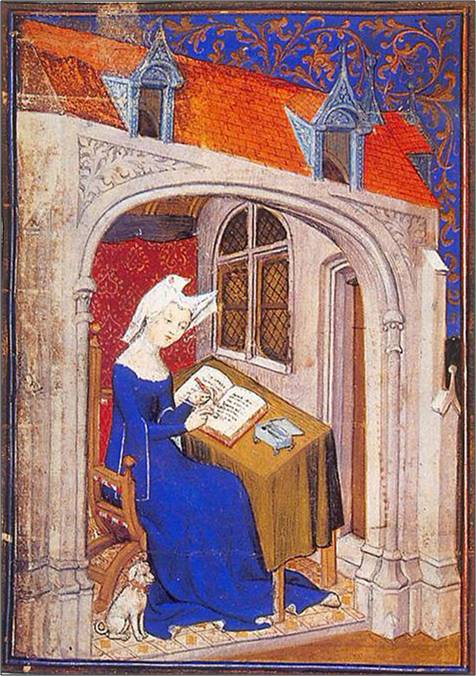

Sofonisba Anguissola self-portrait 1561

Chadwick notes that “among the small group of documented

self-portraits from the period is a “self-portrait of 1561” depicting the

artists as a “serious, conservatively dressed young woman at the keyboard of a

spinet” and so it evident that a great care was taken to create a self-image

that was reflective of herself (79). Again, the presence of the musical

instrument may show Anguissola’s skills as a member of a cultured noble family

at a time when musical accomplishment, long recognized as desirable for

noblemen and women, was becoming a mark of culture for artists of both sexes.

It is important to note that Anguissola was very influential and has indeed

made a great mark in the arts world. Here, Chadwick states that “ her example

opened up the possibility of painting to women as a socially acceptable

profession, while her work established new conventions for self-portraiture by

women and for Italian genre painting” and this makes one of the leaders in arts

movement (77).

Self Portrait 1554

Not only was Sofonisba Anguissola influential within her

community, but she was one of the first female artists to receive international

renown. Word of her talents spread when she was being taught by one of the most

influential artists of the Renaissance, Michelangelo himself.

Gertrude Käsebier

American, 1852-1934

Gertrude Käsebier was one of the most influential American

photographers of the early 20th century. She was known for her evocative images

of motherhood, her powerful portraits of Native Americans and her promotion of

photography as a career for women. On her twenty-second birthday, in 1874, she

married twenty-eight-year-old Eduard Käsebier, a financially comfortable and

socially well-placed businessman in Brooklyn. Käsebier later wrote that she was

miserable throughout most of her marriage. She said, "If my husband has

gone to Heaven, I want to go to Hell. He was terrible…Nothing was ever good

enough for him.” At that time divorce was considered scandalous, and the two

remained married while living separate lives after 1880. This unhappy situation

would later serve as an inspiration for most of her striking works as a

feminist. Gertrude Kasebier, while studying painting in her late thirties,

shifted her interests to photography. With a minimum of professional training,

she decided to become a portrait photographer and opened a studio in 1897.

Success came very quickly and she was recognized as a major talent by Alfred

Stieglitz who brought her into the Photo-Secessionist group and reproduced a

number of her photographs in the first issue of Camera Work. Gertrude Kasebier,

was well known for her work in portraits, employing relaxed poses in natural

light. She emphasized the play of light and dark, and allowed the sitter to

fill the frame so little room was left in the edges of the photograph. In

addition, Gertrude Kasebier was very creative and talented in the printing

process. Her background in painting gave her the ablility to manipulate the

surface of her photographs producing beautiful images that often have a

painterly quality. The University Gallery at the University of Delaware is the

repository of the largest collegiate collection of Gertrude Kasebier

photographs. Barbara Michaels wrote a book on Gertrude Kasebier in 1991

entitled, Gertrude Kasebier: The Photographer and Her Photographs. Käsebier

generally printed in platinum or gum bichromate emulsions and frequently

altered her photographs by retouching a negative or by rephotographing an

altered print. She was the leading woman pictorialist photographer of her day

and, as a married woman with children who attained success and fame, she became

a model for others, including Imogen Cunningham.

Gertrude Käsebier

“Blessed Art Thou amongst Women”, 1899

Here, two generations are dramatically contrasted. The

mother in a white flowering dress appears as an “angel in the house”, the

Victorian ideal of the true woman who devotes her life to family and

domesticity. She is contrasted to her daughter dressed in black and standing

confidently in the doorway, a symbol of transition. The daughter is about to

leave the security and confinement of home, suggesting a radically different

life than that of her nurturing and subservient mother.

Marina Abramović- Performance Artists

Marina Abramović was born November 30, 1946 in Belgrade,

Serbia and is a New York-based Serbian artist who began her career in the early

1970s. Active for over three decades, she has recently begun to describe

herself as the "grandmother of performance art." Abramović's work

explores the relationship between performer and audience, the limits of the

body, and the possibilities of the mind. To test the limits of the relationship

between performer and audience, Abramović developed one of the most challenging

(and best-known) performances. She assigned a passive role to herself, with the

public being the force which would act on her. As a pioneer of performance art,

Marina Abramović began using her own body as the subject, object, and medium of

her work in the early 1970s. Visitors and art enthusiast are encouraged to sit

silently across from the artist for duration of their choosing, becoming

participants in the artwork. This makes her one of the most engaging artists in

arts and without question one of the seminal artists of our time.

Marina Abramović

“Portrait with Flowers”, 2009.

Black-and-white gelatin silver print

Since the beginning of her career in Yugoslavia during the

early 1970s where she attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Belgrade, Abramovic

has pioneered the use of performance as a visual art form. The body has always

been both her subject and medium. Exploring the physical and mental limits of

her being, she has withstood pain, exhaustion, and danger in the quest for

emotional and spiritual transformation. Abramovic's concern is with creating

works that ritualize the simple actions of everyday life like lying, sitting,

dreaming, and thinking; in effect the manifestation of a unique mental state.

The Guerrilla Girls' Bedside Companion to the History of

Western Art. New York: Penguin, 1998. Print

Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. New York, NY:

Thames and Hudson, 1990.Print.

Newark Museum, Angels and Tomboys, Women in front and behind

the camera

http://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/a/anguisso/sofonisb/index.html

http://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/a/anguisso/sofonisb/index.html

http://www.leegallery.com/gertrude-kasebier/gertrude-kasebier-biography

http://www.moma.org/collection/artist.php?artist_id=3008

www.leegallery.com